A blog by Helena.

Relational Schools

My belief in the power of relationships for learning has been the cornerstone of my career as an educator and school leader.

In my early days in the profession, I quickly recognised the importance of building rapport with students and colleagues as the foundation of effective teaching. This become a research interest when I completed a part time Master’s degree as a middle leader: teacher-student relationships was the focus of my literature review and the conditions for teacher collaboration was my thesis subject.

As a senior leader I was involved in a research pilot with the Relational Schools project, an offshoot from the Relationships Foundation. I found myself co-ordinating teacher-led research, contributing a chapter to the book and becoming the poster girl for The Relational Teacher.

As well as making me self-conscious about my double chin, this experience solidified for me the indisputable fact that prioritising relationships in schools is fundamental to successful learning.

This may feel like common sense, however, until relatively recently, there’s been very little deliberate training and understanding of relational practice in the education sector.

Paul Dix’s books have shone a light on the importance of adult behaviour and care to support positive behaviour in school. The roll out of trauma-informed approaches to behaviour management, such as recovery through relationships, has highlighted the important role that relationships with trusted adults play in formative education, especially for our most vulnerable young people.

Most professionals would concur in the importance of relational approaches, but it’s still largely left to chance and considered an implicit personality trait. Students may favour teachers they consider to have a positive relationship with, and teachers will be praised for their interpersonal skills, but it’s not common practice to codify. Behaviour management and pedagogy still typically tends to favour the process over people, and systems over relational synergy.

There can be a lazy binary assumption that caring about relationships means compromising on high standards. Meanwhile, the implementation of Lemov’s ‘warm strict’ approach in schools has led to some interesting interpretations of the concept. A sanctions driven approach conducted with a smile does not a relationship make. The absence of genuine warmth and care can leave us in ‘manipulative insincerity’ territory of Kim Scott’s ‘Radical Candour’.

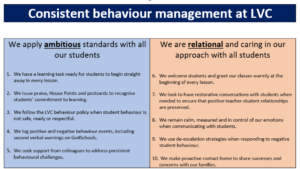

I believe that it is possible and desirable to maintain clear expectations and consequences while also fostering a caring and supportive environment. We have attempted to achieve this sweet spot in our approach to behaviour management at my school. We complement the regular process-driven aspects with an explicit focus on being relational and caring in our approach.

Our commitment to being a relational school explicitly features in our values and is framed within our culture of care. We are proud to be a relational, friendly, caring school operating on a human scale. Our recruitment processes, policies, induction and staff training feature the importance of relationships. ‘Relational’ is a word that staff regular using to define our ethos. It is a way of being.

As a teaching head, I still practise what I preach as a relational teacher but also emulate this approach as a relational leader. Leadership practices prize relationships through being intentional about building relational trust amongst colleagues.

I was once referred to by a highly esteemed colleague as ‘fluffy and formidable’. I’m proud of this epithet; it encapsulates my empathy and drive for high standards. Relationships and rigour are not mutually exclusive, they are complimentary elements.

Creating a sense of belonging has become an imperative in our communities. Trusting, positive relationships are at the heart of creating psychological safety for young people and the adults in our schools in which to do their best learning and work.